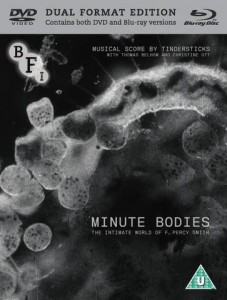

Minute Bodies

Minute Bodies: The Intimate World of F. Percy Smith UK. DVD. BFI. 55 mins. £14.99

About the Reviewer: Ian Christie is Professor of Film and Media History, Birkbeck College, University of London.

Percy Smith was one of Britain’s most successful filmmakers, although he is rarely hailed as such. A pioneer of time-lapse photomicrography, he practised his craft from 1908 until shortly before his death in 1945, finding a succession of sponsors who paid him to do what he was happiest doing. These stretched from the early distributor Charles Urban, a passionate believer in the power of non-fiction film who ‘discovered’ Smith in 1908, through to Gaumont-British Instructional, a subsidiary of the parent company, who were still commissioning his ‘life cycle’ series in wartime Britain. Smith’s innumerable films – he made some 50 for Urban alone – could be as short as three minutes, but typically ran for ten, and fitted neatly into cinema programming’s slot for ‘interest films’, framing the main feature attraction.

In recent years, the historian of science films, Tim Boon, has been at pains to identify how Smith fits into our current understanding of science and its popular communication – as he does in an essay accompanying this new DVD. Boon quotes Smith’s self-description of himself as a ‘dabbler’ in comparison to professional scientists, but not to imply any lack of professionalism in Smith’s painstaking records of plant and insect life. Indeed some of Smith’s earliest time-lapse works, such as The Birth of a Flower (1910), have apparently never been out of distribution, having survived every change in format from mute 35mm to a current 2K digital scan.

In recent years, the historian of science films, Tim Boon, has been at pains to identify how Smith fits into our current understanding of science and its popular communication – as he does in an essay accompanying this new DVD. Boon quotes Smith’s self-description of himself as a ‘dabbler’ in comparison to professional scientists, but not to imply any lack of professionalism in Smith’s painstaking records of plant and insect life. Indeed some of Smith’s earliest time-lapse works, such as The Birth of a Flower (1910), have apparently never been out of distribution, having survived every change in format from mute 35mm to a current 2K digital scan.

The disciplined patience that enabled Smith to record every kind of organic growth, working in his own North London garden with simple apparatus that he had often built himself, yielded images that are, literally, timeless; and, fortunately, were seen as worth preserving, at a time when little film was archived. But what has dated is the style of presentation that enabled these observational gems to masquerade as Odeon entertainment. Their often ludicrous library music, and the plummy tones of a narrator coyly describing the mating customs of frogs as ‘wooing’, may have some period charm, but is unlikely to win Smith legions of new admirers.

What may do so, however, is this innovative compositing of footage into a new work by Stuart Staples the founder of indie music band Tindersticks, who are probably best known in the film world for their soundtracks for Claire Denis. Staples describes how he was drawn into exploring the Percy Smith archive by composing spec accompaniments for these ‘microscopic landscapes’. The end-result is a 50-minute journey through the imagery of about 15 of Smith’s films, with an eclectic accompaniment of soundscapes that combine conventional instruments with Christine Ott’s Ondes Martenot – an early French electronic instrument that has turned up in such diverse contexts as Hitchcock soundtracks (Spellbound, The Birds), the modernist concert music of Olivier Messaien, and Jonny Greenwood of Radiohead.

Minute Bodies. Image courtesy of the BFI.

Since the DVD also includes eight of Smith’s films in their original form, from the early The Birth of a Flower up to Life Cycle of a Newt (1942), there is the opportunity to compare these with Staples’ and his fellow musicians’ atmospheric treatment. Stripped of their period framing and discourse, these do indeed offer ‘landscapes’: the predominant experience is of ‘entering’ the films’ worlds, and becoming intrigued by their extraordinary textures.

The nearest historic equivalent, and perhaps a relevant comparison, would be the natural history films of Jean Painlevé, whose career in marine cinematography started in 1927 and therefore overlapped with Smith’s. However Painlevé never had to work in commercial cinema (as the well-connected son of a former French prime minister), and was able to use avant-garde music and jazz as accompaniments to films such as The Stickleback’s Egg and The Sea-Horse (one of his composers, Edgar Varèse, also used the Ondes Martenot). This combination has long been appreciated, giving him a cultural following and regular gallery exhibitions (as at the Ikon gallery in Birmingham in 2017). Might Stuart Staples’ evident enthusiasm for Percy Smith belatedly give this unassuming Londoner, who left school at 14, something of the same cultural cachet? Staples is frank about his ambition for the man and his films: Minute Bodies ‘invites Smith’s work to breath and exist in the present… His work transcends the constraints of its time, and now it teaches us about patience, commitment, ingenuity and determination.’ In this impressive release, he seems to be following in the curatorial footsteps of fellow indie musicians Bob Stanley of Saint Etienne and British Sea Power, who have also devoted their energies, and hopefully brought their following, to celebrate neglected areas of film history. As an off-shoot of the ‘live silents’ movement to bring silent-era cinema to new audiences, and also a showcase for the BFI’s continuing commitment to restoring more than merely feature films, this is decidedly to be welcomed.

Ian Christie

Learning on Screen

Learning on Screen