Make More Noise!

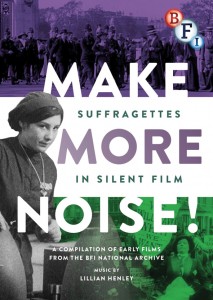

Make More Noise! Suffragettes in Silent Film, BFI, DVD, 71 mins, £19.99.

About the reviewer: Kristyn Gorton is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television at the University of York. She teaches film and television history and theory and Screenwriting. Her published works include Theorising Desire: Freud, Feminism and Film (Palgrave, 2008) and Media Audiences: Television, Meaning and Emotion (Edinburgh University Press, 2009). She is currently working on a project titled Inheriting British Television: Memories, Archives and Industries for the BFI.

About the reviewer: Kristyn Gorton is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television at the University of York. She teaches film and television history and theory and Screenwriting. Her published works include Theorising Desire: Freud, Feminism and Film (Palgrave, 2008) and Media Audiences: Television, Meaning and Emotion (Edinburgh University Press, 2009). She is currently working on a project titled Inheriting British Television: Memories, Archives and Industries for the BFI.

2014 marked the 40th anniversary of Shoulder to Shoulder, the 1974 BBC TV series centred on the struggle for women’s right to vote. A symposium to mark the event was held at Birkbeck, University of London, with cast and crew from the series along with academics. As the organisers of the symposium, Vicky Ball and Janet McCabe, noted in a piece for The Conversation, there has been something of a ‘resurgence of media engagement with the suffragettes’ (https://theconversation.com/lets-hope-that-the-cultural-return-of-the-suffragettes-lasts-this-time-26657) such as Clare Balding’s Channel 4 documentary Secrets of a Suffragette and the BBC 4 sitcom Up the Women, written by and starring Jessica Hynes. Indeed, Up the Women aired to coincide with the centenary of the death of Emily Wilding Davison. So the obvious question is, why now? If you look at what has driven the women writing and producing these pieces, including Sarah Gavron, director of Suffragette, it seems both to come from a desire to tell a story about which there is still so little information and/or to discover something about which they feel they didn’t learn enough at school. In her article in the Women’s History Review, Sarah Gavron notes the absence of a feature length film on the suffragettes and explains that she wanted to make ‘a narrative film that could work for the big screen’ (2015, 986).

Although Suffragette was the first feature length film to depict the movement on the big screen, suffragettes have appeared on film before now. To compliment the release of Suffragette, Margaret Deriaz and Bryony Dixon, the curator of silent film at the BFI National Archive have put together an excellent collection titled Make More Noise! Suffragettes in Silent Film. Taking as their point of departure Emmeline Pankhurst’s message to ‘make more noise than anybody else,’ the DVD is a compilation of over 20 films from the Archives, including documentary, newsreels and comedy– what Dixon refers to as ‘unrestrained girl power’ (5) – giving us a broader perspective of how women were seen on screen.

Although Suffragette was the first feature length film to depict the movement on the big screen, suffragettes have appeared on film before now. To compliment the release of Suffragette, Margaret Deriaz and Bryony Dixon, the curator of silent film at the BFI National Archive have put together an excellent collection titled Make More Noise! Suffragettes in Silent Film. Taking as their point of departure Emmeline Pankhurst’s message to ‘make more noise than anybody else,’ the DVD is a compilation of over 20 films from the Archives, including documentary, newsreels and comedy– what Dixon refers to as ‘unrestrained girl power’ (5) – giving us a broader perspective of how women were seen on screen.

As Dixon explains: ‘the idea here is to focus on the story of the films of the suffragette movement in Britain and to juxtapose that, sometimes stark, actuality with the anarchic and joyful comedians in the pre-war years’ (6). The compilation includes excerpts from the Tilly series (about 20 were made in 1911 and 1912) featuring Tilly and Sally, two young ladies whose irreverent behaviour and ‘wild antics’ demonstrate ‘that such unconstrained behaviour by females could at least be imagined, if not realised’ (Dixon, 11).

From the first portrayal of suffragettes on film in 1899 in Women’s Rights – featuring two men in drag gossiping and posing as suffragettes – to Wife the Weaker Vessel in 1915 where we see a woman pretend to be weak, ladylike and demure before marriage and then to turn on her husband after marriage, leaving him with the baby and going to play golf, we are offered a rare view of how women’s independence was featured on screen at the turn of the twentieth-century.

The DVD is accompanied by an illustrated booklet which includes essays by Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, Bryony Dixon and Lillian Henley (composer and performer of the film score). These essays help to situate viewers in relation to the history and importance of the collection and of the suffragette movement itself. Additionally, there is a short explanation and guide to each excerpt screened.

The compilation is essential viewing for those teaching women’s history and film studies. And because it contains a variety of cinematic forms and styles, it points to a range of issues that could be addressed both with students and for research purposes. This DVD illuminates the importance of the suffragette movement to early twentieth-century British history and film. It should also remind us that although progress has been made, we still have a way to go. As Gavron points out: only four to ten percent of films are directed by women each year (2015, 993). The DVD is a brilliant resource; use it to teach your students about the past so that they can help to change the future.

Kristyn Gorton

Learning on Screen

Learning on Screen