Virtual Rome

A vivid visual reconstruction can help to express the complex findings of archaeologists and historians in an accessible, engaging way. Dr Matthew Nicholls, University of Reading, presents his own work in the field.

About the Author: Dr Matthew Nicholls is Associate Professor in the Department of Classics at the University of Reading. Matthew currently teaches CL2RE Roman Empire and CL3RC Roman Cities. These courses reflect his interest in the political and social history of the Romans and the way that the built environments of Rome and cities around the empire expressed their values and priorities. He also directs Reading’s unique City of Rome MA programme and provides much of the teaching for it, alongside Dr Annalisa Marzano and other colleagues. Matthew is currently working on a book on public libraries in the Roman world for Oxford University Press. His publications include:. 30-second Ancient Rome (Ivy Press, 2014).

About the Author: Dr Matthew Nicholls is Associate Professor in the Department of Classics at the University of Reading. Matthew currently teaches CL2RE Roman Empire and CL3RC Roman Cities. These courses reflect his interest in the political and social history of the Romans and the way that the built environments of Rome and cities around the empire expressed their values and priorities. He also directs Reading’s unique City of Rome MA programme and provides much of the teaching for it, alongside Dr Annalisa Marzano and other colleagues. Matthew is currently working on a book on public libraries in the Roman world for Oxford University Press. His publications include:. 30-second Ancient Rome (Ivy Press, 2014).

I research and teach the history of ancient Rome, and Roman architecture, at the University of Reading. This is naturally a very visual subject. From the grandest public monuments of the Forum and Palatine to the everyday back streets, warehouses, and multi-storey apartments of the ancient city, the archaeological source material lends itself to visual study and interpretation. Reconstructing the way this enormous, complex city appeared and functioned has always been a goal of archaeologists and ancient historians, and visual methods – from archaeological plans to watercolours to physical models in plaster and cork – have long been part of their repertoire.

… students, familiar with high-quality visualisations, respond particularly well to immersive 3D reconstructions used as learning tools

Visiting Rome in person is the best way to get a sense of the city’s history, and over the years I have led several study trips around its sites. Such trips are not possible for everyone, though, and the city’s ruins do sometimes need interpretation – students or tourists can find the remains impressive but confusing. Black and white line illustrations or archaeological plans, which tend to be used by existing archaeological guides to the city, are helpful but can be difficult for non-specialists to interpret or match to what they see on the ground. Both on site and back in the classroom or library, a vivid visual reconstruction can help to express the complex findings of archaeologists and historians in an accessible, engaging way. Today’s students, familiar with high-quality visualisations from film, computer games, and television, respond particularly well to immersive 3D reconstructions used as learning tools.

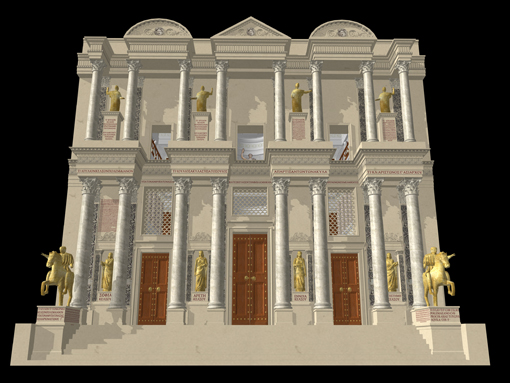

Digital modelling now offers a powerful new way of creating this sort of visual material, increasingly accessible to those who, like me, have no formal background in digital graphics work. I began to experiment with digital reconstruction during my DPhil work at Oxford, using free and easily-learned modelling software like SketchUp to create digital representations of individual structures that I was working on. In particular I wanted to illustrate how I thought ancient public library buildings functioned – how they appeared to visitors, where the book scrolls were kept – and for this purpose pictures were at least as useful as written descriptions.

The Library of Celsus, Ephesus. Modern Austrian archaeologists have re-erected the facade, and this digital model adds interior and exterior features. (image © Dr Matthew Nicholls)

Learning on Screen

Learning on Screen