Science on Screen

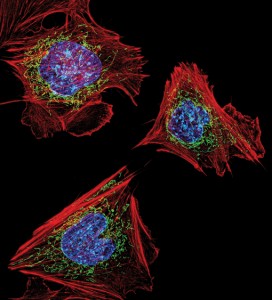

Fibroblast cells with nuclei in blue, mitochondria in green and the actin cytoskeleton in red. (2014 © Flickr / ZEISS Microscopy / CC attribution 2.0)

Creativity

To begin with, consider the importance of creativity. If the suggestion had been made that we should routinely replace our lectures with hours of students sitting passively watching a screen, then I would share any scepticism regarding the value of this approach. However the use of a carefully chosen clip can introduce a new dynamic to a lecture or tutorial. Short extracts can be employed in a variety of ways.

The most obvious use of a clip would be to illustrate some factual point. Rather than describe the processes involved in preimplantation genetic diagnosis, for example, I can include a two-minute clip from Robert Winston’s series A Child Against All Odds (2006), which shows the procedure. Similarly, a short section on the role of cilia in determining the layout of body organs, from Countdown To Life: The Extraordinary Making Of You (2015), presented by Michael Moseley, might help enrich a lecture on the diverse roles of microtubules.

Alternatively, a clip might be used as a scene-setter at the beginning of a session. I have used a couple of short sections from the James Bond film Die Another Day (2002), in which the proprietor of a secretive Cuban clinic explains that gene therapy involves ‘introduction of new DNA from healthy donors; orphans, runaways, people that won’t be missed.’ In this way he is able to transform North Korean Colonel Tan-Sun Moon into British aristocrat Sir Gustav Graves.

Of course this is abject nonsense – gene therapy is something entirely different. But that is exactly the point. This ridiculous storyline serves as a humorous introduction to a lecture when we look in more detail at what gene therapy actual involves and the difficulties that have hampered introduction of far less ambitious changes to the human genome.

Making use of news footage, in this case the rather more tragic case of Eloise Parry, can be used to bring human interest to a lecture on mitochondrial uncoupling. This young woman bought ‘DNP’ (2,4-dinitrophenol) online as an aid to slimming and took several pills in quick succession, triggering a fatal metabolic response. Alternatively a lecture on muscle biochemistry might benefit from inclusion of news reports about an improved technique for determining the concentration of troponin in the blood of a patient with a suspected heart attack.

Thirdly, a clip might be used as a discussion starter. For several years I have run a workshop on experimental design for first year undergraduates, in which I have used a section from the populist science series Brainiac: Science Abuse. In the clip, presenter Richard Hammond supervises an experiment that he concludes ‘proves’ humans can smell fear. Of course the method shown does nothing of the sort, even if we put to one side philosophical debates about the notion of proof.

Once again, however, the poor quality of the science is exactly the point. Students are asked to watch the clip and keep an eye out for aspects of the experiment that are good, and those features that are less good. These observations are then collated, before the students are set the task of working with their neighbours to design a better study posing the same question.

Learning on Screen

Learning on Screen