Bible cinema … in the beginning

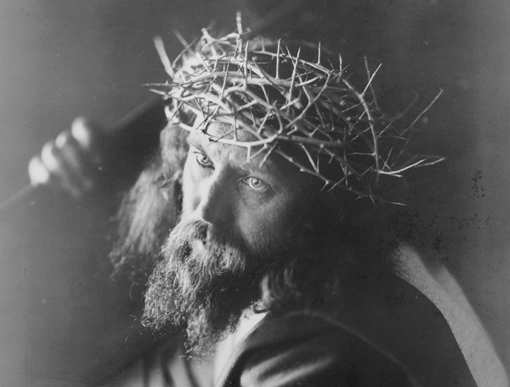

Representation of Christ from the Oberammergau Passion Play circa 1910 (image © F. Bruckmann A.-G., München / Library of Congress / CC attribution)

Shepherd’s book is broadly chronological and deals with less well-known films as well as the already-established industry milestones, which are viewed again with fresh eyes. Twenty years ago Roberta Pearson and William Urricchio established the place of Vitagraph’s Life of Moses (1909-10) within the company’s economic strategy, but their corporate analysis didn’t – for very obvious reasons – contextualise the film within the already significant tradition of cinematic representations of Moses. Similarly, Shepherd revisits the earliest screenings of Passion Plays in America, expanding on prior work by examining the scripts from which those presenting these potentially contentious images worked to explain action and offset potential objections. The earliest such presentations – following on from a tradition of magic lantern presentations – showed American audiences images of Passion plays performed in Horitz or Oberammergau and it becomes clear from the contextualising materials that audiences were left in no doubt that they were not watching a representation of Jesus per se but a representation of a sacred European play (so any theological outrage should be directed towards the European originators not the American exhibitor). The broadly chronological approach – though chapters are also organized thematically – means that Shepherd well charts the waxing and waning of international influences. Thus, as the influence of French cinema on American film production declines, D. W. Griffith takes inspiration from Italian epics. This was a period when the biblical film – not yet an epic, perhaps, but definitely punching above its weight in terms of length and scale – was tied intimately to all developments in film. That, and the breadth of Shepherd’s knowledge, means that the book can be read as an oddly skewed history of the medium in the early years. The obvious absence in the book, passion plays aside, is coverage of the many films depicting Christ himself (or Himself), the high wire of western religious representation. This is something Shepherd will presumably rectify with the same thoroughness on display here in 2015 when Routledge publish a collection of essays on the theme, which he has edited.

Nor will the research end there, I suspect. Shepherd concludes his book with a long list of future directions that the analysis of early biblical cinema might take, including that of its relationship to the explicitly evangelical early Christian film industry. This non-mainstream area of filmmaking, with its own systems of production and exhibition, is the explicit subject of a several volume history currently being compiled by Terry Lindvall under the title ‘Sanctuary Cinema’, the first volume of which covers roughly the same years as Shepherd’s book, finishing in the 1920s when radio established itself as the Christian medium of choice.

Would a Film Studies academic want to take this up as an area of study? I have my doubts, but perhaps a better question is whether American cinema will force their hand? Christians are openly sought as an audience for feel-good against-all-odds movies – The Blind Side (2009) – or violent action pics – The Book of Eli (2010); The Passion of the Christ (2004) – and biblical epic (Ridley Scott’s retelling of Moses, Exodus: Gods and Kings will hit cinemas in December, Ben Hur is due (again) in 2016). Explicitly Christian cinema has had a good year at the US box-office in 2014 with films like God’s Not Dead and Heaven is for Real and even got a release around some of the UK’s independent cinemas. The world of silent biblical cinema is one where Christian themes are explicitly tied to the mainstream. Its research is obviously an historical project, but it may throw up more pointers to the future than we think.

Dr Miles Booy

Learning on Screen

Learning on Screen