BBFC: Learning from the Past

There were also issues relating to localised censorship and regional differences, as well as a lack of a standard system for the consumer and filmmaker. Such issues were live even before the First World War and the BBFC was set up by the film industry in 1912 to standardise decisions and ensure uniformity in film classification. Local Authorities retain powers, to cut, amend, reclassify or even ban works, though in practice this is rarely used outside of film festivals where works are screened sometimes months before they are submitted for classification and go on general release.

The oldest files and ledgers provide interesting titbits of information about the early BBFC, but also huge mysteries. What sort of people were the censors? Were they vicars? Were there any female censors?

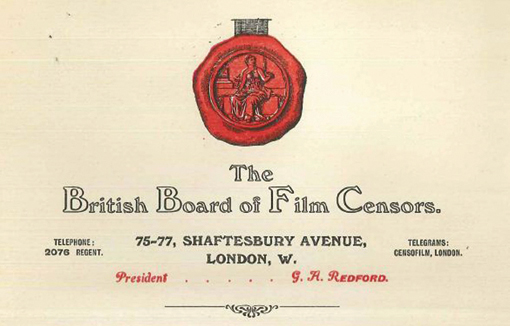

The first BBFC President was G.A Redford and the first Secretary was J. Brooke Wilkinson. In the early years there were only four examiners and they viewed around 120 films a week. Films were projected side by side, an interesting concept for modern examiners who might baulk at the interference and distraction of setting another screen flickering whilst trying to view and classify another.

In terms of the mixture of examiners, by the early 1920s TP O’Connor, a towering figure in the BBFC’s history, spoke about the appointment of a ‘Lady Examiner’ following public calls for a woman’s voice in the process of censorship. He also refers, in an address to the industry, to the wide variety of distinguished candidates for the examiner’s role, and for his decision to employ men of high education and ‘sound judgement’.

There are only some answers to obvious questions. Forty films received classification certificates on the first day of 1913. But there’s no single first film rated. First on the list is About Mary of Briarwood Dell, though the exact fate of this and other titles from those early days such as Aquatic Elephants, or Interrupted Honeymoon, we will only ever be able to guess. We do know all films that day were passed U, though there was an A certificate for films recommended for adult audiences.

Some film titles can only be guessed at because of now illegible handwriting. Film archivists and historians like those at the BFI British Silent Film Festival have worked with our archive team to help decode them. Handwriting analysis isn’t restricted to silent movies. All BBFC registers, large bound books noting films, their titles and certificates (and cuts) were handwritten from 1913 until 1997.

Guesswork is key as most of the oldest film files, including details of cuts and rejections (then called ‘exceptions’) were ‘destroyed by enemy action’ in the Second World War. Anonymity for examiners was strong from the BBFC’s inception and there is little record of who all the examiners were.

Perhaps the best known source of information on the early days of the BBFC is the detailed literature, speeches and analysis, by T P O’Connor, the most famous being his 43 grounds for deletion. Historically the BBFC did not have written rules or Guidelines. Today the BBFC works to published Guidelines based on large scale public opinion research, specialist research and UK law. The absence of these in the early years of the BBFC was in contrast to the position of the US censors who developed the Motion Picture Production Code. Sometimes referred to as The Hays Code, it was introduced in Hollywood by the Hays Office in 1930.

Learning on Screen

Learning on Screen