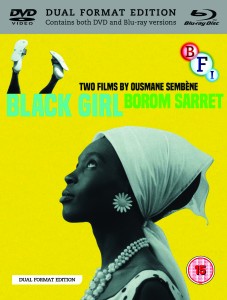

Black Girl/Borom Sarret

Black Girl/Borom Sarret 2015. GB. DVD. BFI. 80 mins. £19.99.

About the Reviewer: David Murphy is Professor of French and Postcolonial Studies in the School of Arts and Humanities at the University of Stirling. He is the author of two monographs, Sembene: Imagining Alternatives in Film and Fiction (James Currey, 2000), and (with Patrick Williams), Postcolonial African Cinema: Ten Directors (Manchester University Press, 2007). He is also co-editor of several collections of essays: with Aedín Ní Loingsigh, ‘Thresholds of Otherness’ (Grant & Cutler, 2002); with Charles Forsdick, ‘Francophone Postcolonial Studies’ (Arnold, 2003), and ‘Postcolonial Thought in the French-Speaking World’ (Liverpool University Press, 2009); with Michelle Keown and James Procter, ‘Comparing Postcolonial Diasporas’ (Palgrave, 2009). He completed a British Academy Mid-Career Fellowship (Jan-Dec 2012), which allowed him to complete a monograph on the Senegalese anti-colonial militant Lamine Senghor (Verso, 2013).

About the Reviewer: David Murphy is Professor of French and Postcolonial Studies in the School of Arts and Humanities at the University of Stirling. He is the author of two monographs, Sembene: Imagining Alternatives in Film and Fiction (James Currey, 2000), and (with Patrick Williams), Postcolonial African Cinema: Ten Directors (Manchester University Press, 2007). He is also co-editor of several collections of essays: with Aedín Ní Loingsigh, ‘Thresholds of Otherness’ (Grant & Cutler, 2002); with Charles Forsdick, ‘Francophone Postcolonial Studies’ (Arnold, 2003), and ‘Postcolonial Thought in the French-Speaking World’ (Liverpool University Press, 2009); with Michelle Keown and James Procter, ‘Comparing Postcolonial Diasporas’ (Palgrave, 2009). He completed a British Academy Mid-Career Fellowship (Jan-Dec 2012), which allowed him to complete a monograph on the Senegalese anti-colonial militant Lamine Senghor (Verso, 2013).

Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation has once again demonstrated its commitment to African cinema by restoring two films, Black Girl (1966) and Borom Sarret (1963), by Senegalese director Ousmane Sembene, now released in a handsome DVD/Blu-ray dual-edition by the BFI. The films are accompanied by a series of extras, including two documentary portraits of Sembene and an interview with Thérèse M’Bissine Diop, the star of Black Girl. There is also an informative booklet with material on both the films and Sembene’s career.

Often hailed as the ‘father of African cinema’, Sembene was a Marxist who made a series of powerful, politically committed films across five decades. His short film, Borom Sarret, was the first shot in Africa by a black African. It tells the deceptively simple tale of a down-at-heel cart driver and its picaresque structure allows the director to capture, in a broadly neorealist style – grainy black-and-white images, shot on location in the city streets and an observational attention to the small details of daily life – the harsh realities of postcolonial Dakar. Indeed, neorealism’s DIY aesthetic was a perfect fit for many ‘Third World’ filmmakers in the post-war period, who were often socially committed but struggled to make their work in societies without an identifiable film industry.

Although a closely observed realism would remain a cornerstone of his work, Sembene’s films were more formally hybrid than critics have often allowed, and Black Girl is a case in point. The film captures the mental breakdown of Diouana, a Senegalese maid, whose dreams of a glamorous life on the Côte d’Azur with her French employers are shattered by the mundane reality of a life spent cleaning, cooking and minding the children. The most striking aspect of the film’s narrative structure is the suddenness of Diouana’s fall into despair. There is no attempt to detail a life of drudgery and domestic servitude, instead, Sembene plunges the viewer into a world defined by her sense of anguish and alienation. As she mops the floors, dressed in her tight-fitting white dress with its striking black-and-white patterns, in stiletto heals and daisy earrings, she is a symbol of the cultural alienation produced by the colonial encounter.

Diouana might equally be read as a commentary on the alienation and anxiety produced by mass consumer culture, a theme central to much 1960s French avant-garde cultural production, as, for example, in the films of Alain Resnais or Jean-Luc Godard. This is most evident in the remarkable closing sequence of Black Girl, which like Resnais and Marker’s Statues Also Die (1953) explores the commodification of artworks that had once played a powerfully symbolic role in African societies. After Diouana’s suicide, her French employer travels to Dakar to return her belongings to her family, including a mask she had offered them as a gift. He turns to walk away, but is pursued by the maid’s younger brother holding the mask over his face: as the non-diegetic sound of pounding drums grows louder, a series of tightly edited close-ups and medium shots follows the pair through the shanty-town. The film closes with a close-up of the boy allowing the mask to fall slowly, revealing the distraught face of a grieving, confused sibling.

Diouana might equally be read as a commentary on the alienation and anxiety produced by mass consumer culture, a theme central to much 1960s French avant-garde cultural production, as, for example, in the films of Alain Resnais or Jean-Luc Godard. This is most evident in the remarkable closing sequence of Black Girl, which like Resnais and Marker’s Statues Also Die (1953) explores the commodification of artworks that had once played a powerfully symbolic role in African societies. After Diouana’s suicide, her French employer travels to Dakar to return her belongings to her family, including a mask she had offered them as a gift. He turns to walk away, but is pursued by the maid’s younger brother holding the mask over his face: as the non-diegetic sound of pounding drums grows louder, a series of tightly edited close-ups and medium shots follows the pair through the shanty-town. The film closes with a close-up of the boy allowing the mask to fall slowly, revealing the distraught face of a grieving, confused sibling.

In the mid-1990s, the BFI released two VHS editions of Sembene films – Xala (1975) and Borom Sarret – to coincide with the centenary of cinema celebrations. Scholars of African cinema in the UK have waited more than two decades for a new release so this initiative is to be welcomed with open arms, and it will, I hope, lead to Sembene’s work gaining the place it deserves on the curriculum, not just on African cinema courses but on film courses more widely. The BFI’s mid-90s promotion of African cinema proved a one-off that did not lead to any further releases of classic African films: here’s hoping that this initiative will lead to further DVD packages featuring the work of Mustapha Alassane, Désiré Ecaré, Dijibril Diop Mambety and other great West African directors in the years to come.

David Murphy

Learning on Screen

Learning on Screen