What is Women’s Film History?

Women’s Film History Network-UK/Ireland is an emerging organization open to anyone committed to investigating women’s film history from its early days to the recent past.

About the author: Professor Christine Gledhill is Visiting Professor in Cinema Studies at the University of Sunderland.Her publications include Gender into Genre: Cross-currents in Post-War Cinema (forthcoming, Illinois University Press); Reframing British Cinema 1918-1928: Between Restraint and Passion (2003, British Film Institute); Reinventing Film Studies, edited with Linda Williams (2000, Edward Arnold); Home is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama (1987, British Film Institute).

About the author: Professor Christine Gledhill is Visiting Professor in Cinema Studies at the University of Sunderland.Her publications include Gender into Genre: Cross-currents in Post-War Cinema (forthcoming, Illinois University Press); Reframing British Cinema 1918-1928: Between Restraint and Passion (2003, British Film Institute); Reinventing Film Studies, edited with Linda Williams (2000, Edward Arnold); Home is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama (1987, British Film Institute).

E-mail: christine.gledhill@gmail.com

Women’s Film History Network-UK/Ireland aims to encourage, support and disseminate research into the history of women’s participation in cinema across the full range of activities, including:

producing / directing / scriptwriting / designing / editing / scoring / sound-recording / costuming / distributing / cinema-managing / exhibiting / critical writing / reviewing / performing / activity as audiences and fans

How We Began

The Network emerged as a small, informal group from the Women and Silent Britain day held at the NFT in November 2006. This event, followed by a second in November 2009, responded to American-led initiatives begun in the late 1990s that challenged the absence of women in standard film histories. The establishment of the biennial Women and Silent Screen conferences staged in America, Mexico, Europe and soon in Australia (2013), and the growing body of research recorded by the international Women Film Pioneers Project (see below) reveals women creatively active in every conceivable job associated with cinema. So what had happened in Britain?

The large audience gathered at the NFT registered both surprise and delight at the new discoveries presented of adventurous women who in different ways had participated in the formative days of British filmmaking.

The large audience gathered at the NFT registered both surprise and delight at the new discoveries presented of adventurous women who in different ways had participated in the formative days of British filmmaking. This surge of enthusiasm spurred us to seek funding to establish a British-based Women’s Film History Network. With support from the Centre for Research in Media and Cultural Studies at the University of Sunderland we won an award from the Arts and Humanities Research Council to run a series of Workshops through which to lay the groundwork.

At the heart of these initiatives is the growing recognition that, despite their marginalization in film history, women have been and continue to be involved in cinema in a wide range of roles.

What Is Women’s Film History?

At the heart of these initiatives is the growing recognition that, despite their marginalization in film history, women have been and continue to be involved in cinema in a wide range of roles. However, in formulating network identity we have faced a number of compelling questions and organsational choices. To work through these questions, the first three Workshops brought a range of enthusiasts specializing in women’s history, literary, theatrical and publishing histories, film and media studies together with representatives from archives, libraries, museums and professional organisations as well as from other special interest networks such as Women’s History Network and MECCSA’S Women’s Media Studies and Race Networks. These Workshops focused first on the key question ‘What is Women’s Film History?’; second on the problems of ‘Transnationalising Women’s Film History;’ and most recently on the practicalities of ‘Resourcing Women’s Film History.’

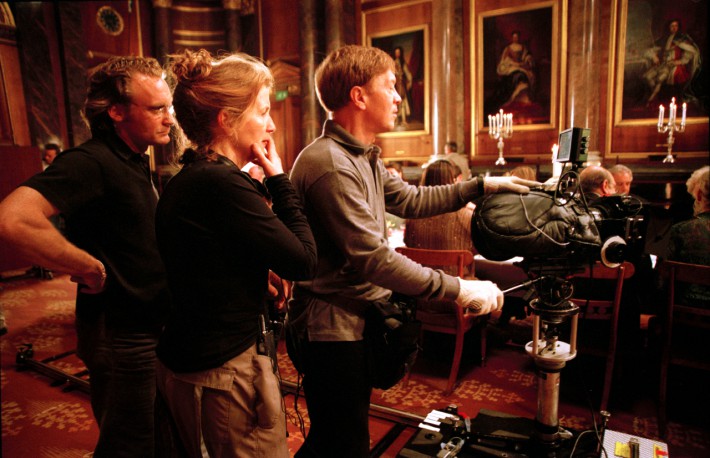

Fiming 'Yes' with L-R: Steadicam Operator Eric Bialas, DirectoR Sally Potter, DoP Alexei Rodionov (© Nicola Dove).

Asking what it means to put ‘women’ in front of film history, the first Workshop questioned whether women’s film history is only a matter of filling gaps in an already established history of male inventors, moguls, and great artists. Or whether posing questions of gender changes the way we do film history and therefore that history itself. In what sense, if at all, does ‘women’s’ film history ‘belong’ solely to women? Asking questions about women opens up dimensions of filmmaking and conceptions of cinema not before perceived or, if perceived, disregarded. For example, we find women in large numbers in roles considered subsidiary: production assistants or secretaries; continuity girl; editor; costume designer; make-up artist; laboratory hand, and so on. If writing history from a woman’s perspective means exploring those roles, it leads us not only to reevaluate the nature of filmmaking but highlights roles in which men also go unrecognized.

The impact of women as audiences and social campaigners, in their own viewing practices, or as imaginary targets for filmmakers and studios … is crucial to cinema’s development as a set of social institutions and creative practices

More challenging, the frequent positioning of women filmmakers as partners–professional or personal–of men, as well as their often factotum-like involvement across studio functions, or in the collaborative independent film workshops of the 1970s and 1980s, demands we conceptualise the collectivity of filmmaking, resisting the search for an ‘onlie begetter.’ The relationship between Alma Reville and Alfred Hitchcock is only the most famous of many creative partnerships. This raises the question of the difference the woman filmmaker makes or is expected to make. In a complicated way we have both to take account of gender as a social determinant and discount it as an unequivocal dimension of creative output. Little separates journalistic surprise that Britain’s ‘only woman director’ of the 1920s should make naval melodramas displaying war-like ‘patriotic fervour’ from recent commentary on Oscar-winning Kathryn Bigelow’s demand for recognition as director of action movies rather than as woman filmmaker. However, once we begin to conceive cinema in a wider social context, then social gendering – as opposed to an essential gender identity – becomes integral to analysis. The impact of women as audiences and social campaigners, in their own viewing practices, or as imaginary targets for filmmakers and studios, or sources of gendered value for social reformers, policy makers and aesthetic theories, is crucial to cinema’s development as a set of social institutions and creative practices.

A second question following the first asks, ‘Is women’s film history only about film?’ Given that many women became involved in filmmaking through working in other media—as writers of adapted material or as scenario and screenwriters, as interior designers and fashion costumiers, as theatrical performers and music-hall entertainers, as journalists and critics, and in the many roles offered by television—women’s film history cannot ignore the institutional and creative relationships between different arts and media. Thus, while focused on film, we invite participation and exchange of perspectives from specialists in women’s history, theatre and literary studies and analysts of the publishing and television industries.

The film industry, film culture and women’s film history reaches beyond national boundaries

The second Workshop, held in collaboration with the Film Division of Columbia University in New York, addressed the internationalism of film history, which raises the question, ‘What does it mean to put “British” in front of film history?’ The film industry, film culture and women’s film history reaches beyond national boundaries through international co-production and creative cross-fertilisation. How to assign national identity becomes problematic, when film workers so frequently cross national borders and women change national affiliations and names. Luke McKernan’s account on his blog, Biscope, of his transnational hunt for Mary Murillo–a prolific and for a while highly paid scriptwriter in Hollywood in the 1910s and early 1920s, demonstrates the challenges presented by women’s cross-border careers. Born Mary O’Connor to Irish parents in Bradford in 1888, she throws the researcher a Latino red herring with the assumed surname, Murillo, and as her Hollywood career came to an end returned to write films in Britain and occasionally France in the 1920s to early 1930s before disappearing from view.

Given the early internationalism of the film industry, the overwhelming presence of American films on British and Irish screens, and more recently the intensification of cross-national co-production and transnational circulation through digital technologies, the question arises whether the organization of film histories in national boxes impedes research and is any longer justifiable. In particular, in the creation of national archives and the writing of national film histories, does ‘nation’ obscure questions of gender? We need ways of thinking, researching and developing inter-archival resources that enable border-crossing, transnationally interconnected histories.

Doing Women’s Film History: Reframing Cinema Past and Future

These questions underpinned the recent landmark international conference, Doing Women’s Film History: Reframing Cinema Past and Future, held 13-15 April 2011 at the University of Sunderland. As on offshoot of the Network and platform through which it can draw in, and from, a wider community, Doing Women’s Film History will become a biennial event, alternating yearly with Women and the Silent Screen. The inaugural conference at Sunderland drew over a 100 delegates, with 70 papers split evenly between 35 UK and 35 overseas papers drawn from 16 different countries. This inspirational event provided testimony, if it was needed, to the searching questions opened up by women’s participation in the cinema’s history, and to the productiveness of trans-national, cross-media, cross-cultural exchanges of research findings, ideas and interpretations. In particular conferences papers, keynote presentations and roundtables enabled exchanges between those involved in the founding ideas and practices of second-wave feminist film groups of the 1970s and 1980s and a younger generation working in changed political, cultural and institutional conditions; between academic researchers (male and female) and women professionals involved in film production, distribution and exhibition; and between scholars and activists situated in different countries or coming from different ethnic backgrounds, who, drawing from diverse intellectual traditions and cultural histories, come through different entry points and with different perspectives to the study of cinema, film history and feminism.

Resourcing Women’s Film History: Making the Network Work

The third of the Network’s AHRC funded Workshops focused on issues of resourcing–especially the possibilities opened up by on-line and digital mechanisms for storing and sharing research findings and ideas–and on models of Network organization. Through this workshop we drew from the experience of participants working in archives, libraries and museums, in different educational sectors, and running other networks: Women’s History Network; MECCSA’s Women’s Media and Race Networks; and the international network, Bildwechsel.

Karola Gramann of the Kinothek Asta Nielsen, Frankfurt at the Doing Women's Film History conference (photo: John-Paul Green)

Following the conceptual ground clearing of Workshops One and Two, and Workshop Three’s review of resource issues and organizational choices, we have identified a set of core activities within a broadly defined remit. Adopting the tag ‘UK/Ireland’ to encompass our various locations in England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic, the Network defines its research interests as British and Irish women filmmakers working in their own regions or abroad and oversees women who work here. The Network is affiliated to the umbrella organization, Women & Film History International and encourages contributions to international initiatives already noted. In particular we are now soliciting contributions to the UK/Irish raft of entries to the Women Film Pioneers Project (an online expandable and updatable digital digest of resources in preparation by the Center for Digital Research and Scholarship, Columbia University).

On the home front the Network seeks to serve a culturally diverse history, making connections with ethnic minority arts and media networks in the UK and Ireland such as MECCSA’s Race Network or writetalklisten. Similarly, we are establishing links with related professional organizations such as Women in Film and Television (WiFTV UK), The Women’s Library, and the BFI’s Screenonline. In this respect the Network’s interest in history is as much its usefulness to the present as uncovering the past. Unlike the international initiatives mentioned, the Network’s remit extends beyond the silent period to women’s work in sound cinema, with a particular concern for the documentation and preservation of the work of the workshops and collectives of the 1970s and 1980s. For women and ethnic minority filmmakers struggling to get work made and circulated now, preserving and making this recent history available is particularly important as a supporting tradition for future generations.

On the home front the Network seeks to serve a culturally diverse history, making connections with ethnic minority arts and media networks in the UK and Ireland

Recognizing the constraints on time and finance once AHRC funding ceases in October, we have been pragmatic in defining network functions and membership structure. Rather than organising a specific programme from an institutional centre, the network aims to stimulate and facilitate a widening web of interrelated activities that by generating knowledge, increase the visibility of women’s filmmaking. To achieve this the Network seeks a flexible mode of membership combined with an organizational centre capable of stimulating and sustaining such activity. The Network is conceived as an umbrella organisation to which any group or individual developing projects on any aspect of women’s activity in and around cinema might affiliate, using the network presence and online communications to circulate projects and events or record research findings and set up collaborations. The Network will provide a home base–a virtual meeting place where research findings can be shared, ideas exchanged and initiatives publicised,. The internet offers the ideal medium for the creation of such a base and an organic mode of organization that can be flexibly inclusive and yet ensure the sustained continuity of core functions supporting evolving activities over time as membership grows and takes the Network in new directions.

To ensure these sustaining functions, a steering group of volunteers will take on particular responsibilities, in pairs or small sub-groups. This will meet three times a year to review and co-ordinate new developments. Steering group membership will be drawn partly from volunteers from the current AHRC funded core or from those who contact as through our current wiki, or from nominations made at the Network’s biennial general meetings hosted by the Doing Women’s Film History conferences. Positions will be held for two years and new nominations called for, voted on and agreed at these conferences. Additionally the Network will hold caucus meetings at relevant events such as Screen conference, Women and Silent Screen (Australia, 2013), British Silent Film Festival, MECCSA conferences in order to publicise existing or initiate new activities, reach a wider audience and broaden membership.

Membership, established by subscribing to the Listserve, is open to anyone committed to contributing to the development of women’s film history, whether academic researchers, film enthusiasts, or family and local historians.

Core functions, identified for development over the next two years include the creation of a website, a listserve, an e-newsletter, and a continuing organisational contribution to the biennial Doing Women’s Film History conference. The Website -rather than an institution or physical location – will function as a virtual centre for the Network and exchanges between its members, requiring a digital programme (probably wordpress) and design that are both user friendly and open to shared use. It is envisaged that the website will contain a Home Page; an ‘About Us’ section, including a Network Members Directory, contacts for Steering Group members, and a link to the Network’s Archive (our current wiki); a News/Noticeboard on which events, conferences, festivals, research proposals, new publications, information sought can be posted; a E-Library containing past E-newsletter editions, book reviews, members’ articles as PDFs; a Resources Section in which new research findings can be posted and links provided to other networks, archives, journals and publication opportunities (e.g. e.g. Genesis; Screenonline; Women and Silent British Cinema website; WiFT, BUFVC; BEV; BECTU; TWL; Feminist Media Studies; MECCSA Women’s Media Studies and Race Networks; Women Film Pioneers Database); and a Contact Us email address.

The Listserve is key to the creation of membership and routine interaction between Network members. Membership, established by subscribing to the Listserve, is open to anyone committed to contributing to the development of women’s film history, whether academic researchers, film enthusiasts, or family and local historians. There will be no membership fee at present, though as the Network develops it may need to set dues. Joining the Listserve will enable members to receive the E-Newsletter three times a year.

Debra Zimmerman of Women Make Movies at the Doing Women's Film History conference (photo: John-Paul Green)

In addition to facilitating these core functions, the Network Steering Group will undertake fundraising and search for sponsorship. If successful, future projects in prospect include the development of a Researching Women Filmmakers Starter Kit, a Programming Package identifying sources of women’s films and related support materials, and Education Packages to support the development of gendered and historical perspectives in the school and college curriculum.

The project of promoting the visibility of women’s participation in film history aims at a number of outcomes: to encourage new historiographic approaches to cinema that are sensitive to gender, class and race; to make the case for the preservation and availability of women’s films and thereby increase programming choice in film theatres, television channels, DVD outlets; to impact on the teaching of film and media in schools and colleges and so, last but not least, to raise the aspirations of young women as potential future filmmakers.

Details of our application to the AHRC Research Networking Scheme to set up the Women’s Film History Network-UK/Ireland, along with the Workshop programmes and full programme and abstracts from the conference, Doing Women’s Film History: Reframing Cinema Past and Future, can be found on our wiki at: http://wfh.wikidot.com.

New participants in the Network are very welcome. If you are interested in joining our mailing list, contributing to the Network’s Steering Group, or undertaking research into the many unrecorded women filmmakers who have worked in the UK and Ireland as part of the Women Film Pioneers Project, please email me at the address below.

Professor Christine Gledhill

AHRC Network coordinator

christine.gledhill@gmail.com

Learning on Screen

Learning on Screen