The Listening Experience

Aims & technical issues involved in delivering the content online

The project team includes staff of the OU’s Knowledge Media Institute (KMi), which pursues cutting-edge research into areas such as semantic technologies and multimedia. They have designed the online entry form to be as intuitive as possible. We were conscious that the form needed to cater for an array of different listening experiences supplied by contributors with varying amounts of information. Each listening experience is unique, not only in the precise detail of the evidence being supplied, but also in terms of the peripheral information that is just as important: for instance, the type of source the experience appears in (such as a letter or diary entry, which might appear in a published book or equally in an unpublished manuscript); when the experience occurred (at a specific time on a single day or over several days, weeks or even years); what the piece of music was, who performed it, where it was performed, and if this differed from where and how it was heard. The evidence might describe an experience of an individual or of a crowd. The listener might not even be mentioned by name, but given a description such as ‘A Shopkeeper’ or ‘A group of soldiers’. Contributors will not necessarily have all of this information to hand. Yet it was important to ensure that the interface was both intuitive and versatile enough to accommodate as much information as they might be able or willing to offer.

… one of the principal ways in which this technical challenge has been met, was through the use of Linked Data

One of the principal ways in which this technical challenge has been met, was through the use of Linked Data. This is about using the Web to connect related data that wasn’t previously associated. So for example, rather than having to type in all of the details of a particular piece of music or listener, the database will use external sources to search against what the contributor has typed. If they are found elsewhere on the Web, the entry form will return these suggestions, saving the user time and effort and forging a relationship between LED data and the external source. If a contributor suggests that the listening experience involved a piece by Dizzee Rascal, the details of this music will be known elsewhere, as will his biographical details, and these can be retrieved using Linked Data.

What is equally impressive – and to our knowledge LED is one of the first projects that uses crowdsourcing to attempt such a thing – is that when ‘new’ data is created within LED’s own platform, this is then accessible via other Linked Data sites. It’s a little like creating a new record on Wikipedia that other sites such as Google can then link to, but more than that, it is a means to building more useful relationships between different bits of data on the Web – try searching on Google for ‘Dizzee Rascal’ or any other known individual and you will see an assortment of information returned on the right hand side, none of which you particularly asked for but which is potentially useful and relevant nonetheless.

Having just completed the first year of the project, the entry form has undergone its initial phase of development and the database is up and running. The LED project team is now inviting you to participate.

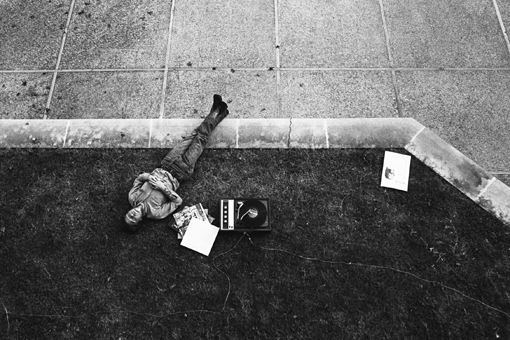

Yes Music in the Amphitheater, students listening to music, 1970. (Photo © Ed Uthman)

Learning on Screen

Learning on Screen