Intelligent Speech

Indeed the extraction of rich information is probably of far greater importance than the two areas where speech-to-text is usually supposed to be of greatest value: search and transcription. Speech-to-text provides an obvious additional element to search, opening up audiovisual content to word-searching alongside traditional text-based resource, but this alone is not enough, particularly where the results continue to be less than 100% accurate. The point is that speech-to-text is about so much more than simply finding a word or phrase in an audio file, useful though this primary function undoubtedly is.

The quest for transcriptions is misleading. Human-generated transcription services (where actual humans transcribe an audio file for you, at so much per hour) proliferate across the Web, and were a technology to be developed that could provide a perfect transcription automatically, then it would big business for somebody. But speech-to-text is not going to yield perfect transcriptions, certainly not any time to soon, if ever. The sheer variety of accents, modes of speech, the number of voices who may be speaking at the same time, all militate against such an ideal. A rough record can be generated, but accuracy rates can range anywhere between 30-80%, depending on the circumstances of the recording. A single voice in a familiar accent speaking directly into the microphone without extraneous noises will generate good results. This is why so many speech-to-text applications have focused on news programming, and it is how subtitles are generated for television programmes (a subtitle operator speaks the words they hear being said on a programme into a microphone, which then uses speech-to-text to create the rough transcript, the voice of the subtitler being easier for the system to understand than the direct broadcast). But unfamiliar accents or multiple voices recorded in more haphazard conditions only demonstrate the limitations of the technology.

The other problem with transcriptions is that they betray a fundamental suspicion of the value of the audio or video record in itself. We should not want to be creating transcripts as a substitute for listening to the original. That is a denial of the very value of the audiovisual record.

… the dream is to have anyone understand anyone else in whatever language they speak simply by speaking to them through their phone

Microsoft, Google and others are looking at speech recognition systems which can open up the vast audiovisual archive that the Internet represents, and have particular interest in allying the technology to translation tools for mobile applications. The dream is to have anyone understand anyone else in whatever language they speak simply by speaking to them through their phone. This Babel Fish vision will undoubtedly be transformative, but we have only to see the limitations of Google Translate in converting one written language to another to realise that these tools will only ever provide approximation rather than exactitude, at least for the foreseeable future.

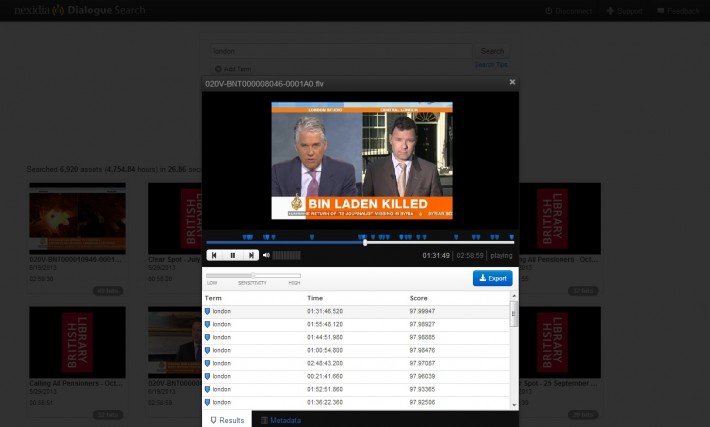

Instead, the practical power of speech-to-text, particularly in an academic setting, must lie with its ability to generate keywords and facilitate entity extraction. We should not look at speech-to-text as generating a full reproduction of the words spoken, but rather as generating a rich set of data which can be linked to particular points in a file and linked out to other resources through open data models (though of course a full transcription will generate such rich data, and more). The BBC World Service prototype demonstrates the great value of extracting keywords in this way (though the keywords do not then link back to time-points in the digital file, which is a limitation), while the GEMS prototype shows how the Linked Open Data model can operate. We should use speech-to-text to uncover the intelligence embedded in digital objects. This will best enable the integration of audiovisual content with other, text-based resources, and will prove of greatest value to academic research in the years to come.

Luke McKernan

There is more information on the Opening up Speech Archives project at www.bl.uk/reshelp/bldept/soundarch/openingup/speecharchives.html.

Learning on Screen

Learning on Screen